Images of Dora

With camera and pencil, artists documented Dora and presented the perspective of the regime and its victims. Some artists left powerful visual evidence of the ambition and efficiency of the high–tech V–2 program and the efforts to sanitize its brutality. Others recorded the intense suffering and death of the prison laborers.

Walter Frentz, known as Hitler’s favorite photographer, was commissioned by Albert Speer, German Armaments Minister, to photograph and film rocket assembly at Mittelwerk, the underground factory at Dora. Speer intended the photos to persuade Hitler to maintain support for the V–2 program. Frentz and a team of assistants visited Dora in early summer of 1944 and took specially staged photographs to showcase the efficiency of forced labor and the vast scale of the cavernous factory. The photographs are significant for their early use of Agfa color film. They are also striking examples of propaganda, showcasing only skilled assembly work, not back–breaking excavation and construction work, and featuring relatively healthy prisoners in clean clothing hand–picked for the photo shoot. The photographs also omit the presence of the SS and Wehrmacht in the factory, as well as the “kapos,” prisoners charged with supervising other prisoners, often with notorious brutality.

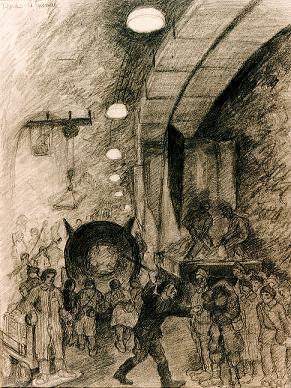

In powerful contrast to the sanitized Frentz photos are the sketches and drawings completed by prisoners who survived Dora. These images feature prisoners engaging in exhausting manual labor under the control of stick-wielding kapos, piles of emaciated dead bodies, corpses burning on open pyres, and public hangings. The artwork was prepared secretly by prisoners who had privileged status based on SS recognition of their distinguished artistic backgrounds, including Léon Delarbre, a painter, museum curator, and member of the French resistance, and Maurice de La Pintière, an art student pinpointed as official portraitist for the camp and also charged with painting barracks. These artists worked in offices, workshops, and supply stores under the supervision of German civilians rather than SS guards, which gave them access to paper such as envelopes salvaged from trash cans, and pencils, some privacy for drawing, and access to hiding places for their images. The artists carefully documented atrocities at Dora to which they were witnesses, even though they personally escaped the worst ravages. At the time of Dora’s dissolution in April 1945, they risked their lives to smuggle the drawings, which they recognized as valuable historical evidence, out of the camp. These artists and others also created additional drawings following the war.

Dora remains an object of fascination and horror today. Tourists and professionals photograph the site and the remaining evidence of the wartime atrocities.

Walter Frentz and Propaganda Photographs

- Official Walter Frentz Website, Featuring Biography, Films, Photography, Publications, and an Archive of his Photographs under “Fotografie” and Zeitdokumentarisches Fotoarchiv”

- Obituary in German Newsmagazine Der Spiegel (in English)

- Article, “Hitler’s Cameraman,” from Der Spiegel, featuring Slide Show of Frentz Photographs; Slide 22 Features Brief Documentary Video in German

- French Website on Forced Labor at Dora Featuring Some Frentz Photographs

- Essay, “Photographing Hitler” on Hitler’s Use of Photographers for Propagandistic Purposes

- The Eye of the Third Reich (documentary film)

Prisoner Artists

- Lengthy Brochure on Nazi Concentration Camps Featuring some Sketches and Drawings from Dora Survivors (in French)

- French Website on Forced Labor at Dora Featuring Some Prisoner Artwork

- Biographical Information on Maurice de La Pintière, the Dora Prisoner and Survivor and Professional Artist Who Created Many Dora Sketches and Drawings

- Website Showcasing Maurice de La Pintière’s Postwar Comic Strips

- Postwar Photo of Maurice de La Pintière at Work

- Biographical Portrait of Maurice de La Pintière with Photograph (in French)

- Brief Biographical Information on Dora Prisoner and Survivor and Artist Léon Delarbre

- Profile of Léon Delarbre Including Drawings and Sketches (from the Main Menu, Click On “Léon Delarbre: Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dora, Bergen-Belsen”)

Online Digital Collections and Databases

- Dora Memorial Website Digital Collection (Click on “Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp Memorial” and then on “Digital Collection”)

- Dora Memorial Photo Index. Includes many Frentz images, plus Images of Region, Key Figures, Some Photos of Prisoners. Indexed by Topic, Photographer, Subject (Directions in German)

- Dora Photographs from “Holocaust Encyclopedia” published by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Photographs of Dora in the mid-1990s by Photographer Al Gilens

- Dora Historical and Contemporary Photograph Set

- Photographs of Dora

- Photographs of Dora, Then and Now

- Photograph Set from Buchenwald Memorial Website, Including Color Photograph of Tunnel Construction by Walter Frentz and Post-Liberation Images Including Color Photo of Soviet Destruction of Tunnel Entrance

- Screen shots from German Documentary with English Notes

- Dora photos labeled in French

- Google Earth Photographs of Mittelbau-Dora Site

- Google Earth Photographs of Mittelbau-Dora Site with Historical Overlays